Story as Ritual

I. The First Reading Isn’t the Real Reading

There are certain books I return to again and again—not just yearly, but weekly, sometimes daily. Not out of duty, not even because I forget (although I do), but because they speak differently each time. Or maybe a different part of me listens each time.

I don’t always read them straight through. I jump to parts, not lines, or quotes, but to passages or chapters. I’m not dissecting to understand the smaller pieces. I’m integrating to resonate with themes. And something always catches. A phrase folds into my mood, or interrupts it. A character’s gesture resonates with a part of me I hadn’t known was listening.

And it’s not that it lands differently than the last time, but it has more of me to land on.

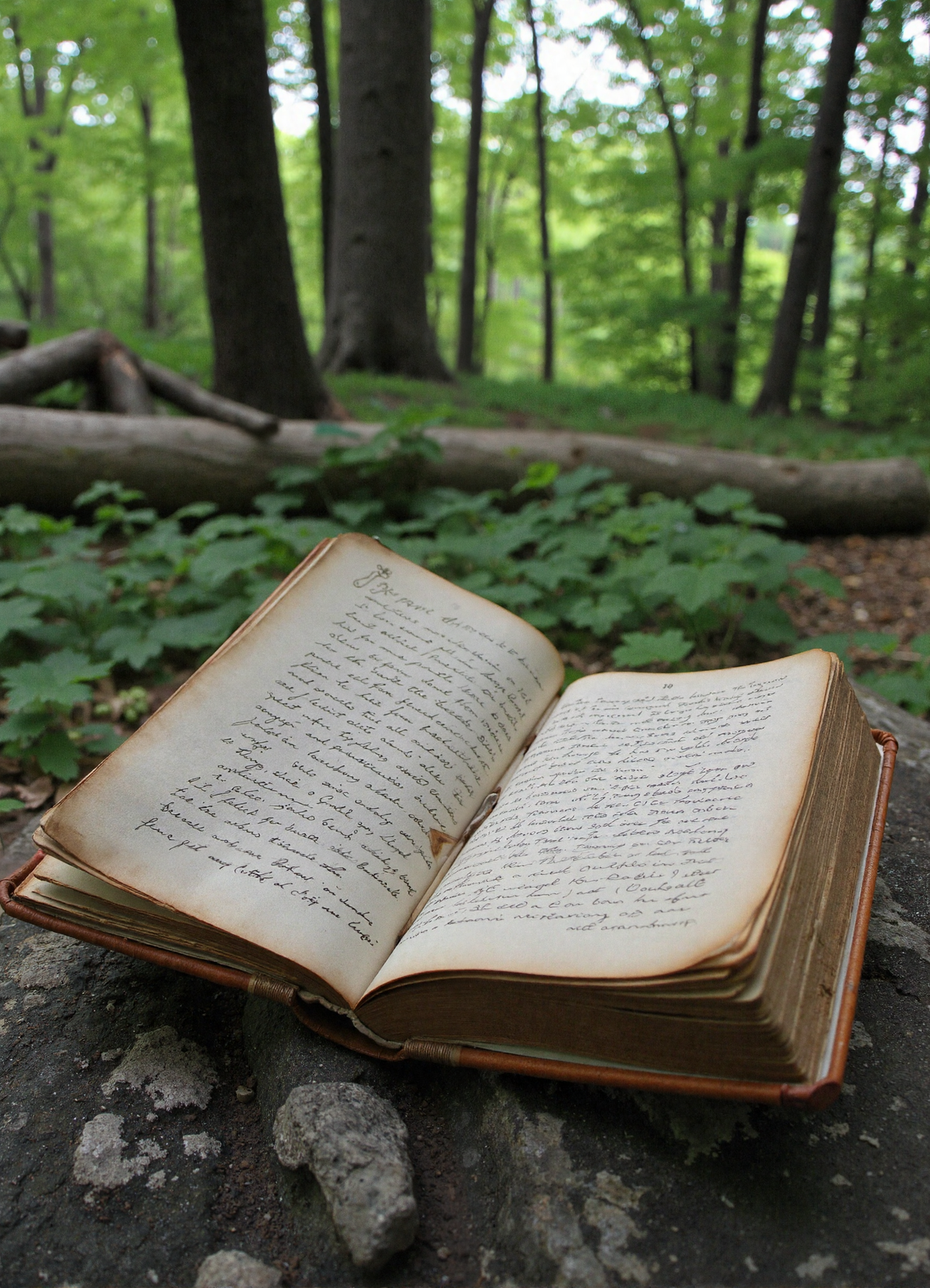

I’ve come to think of this kind of story as ritual reading. Not for study. Not for information. But for contact. These stories don’t wear out. They ripen. What they meant to me at twenty is not what they offer at forty. The words are the same. I’m not. So it’s a different conversation. Think of it as playing the same notes on a different instrument. The notes are the same but not the sound.

This is an essay about that: about the strange, deepening magic of stories we return to. It’s also a quiet manifesto for the kind of stories I try to write—ones designed not for a single reading, but for echo, rumination, and slow unfolding.

If you've ever reread something and felt like you were a different audience—and the story was playing to that new crowd like a good actor would—then you already know this experience. I want to show you why that happens and how I try to write toward it.

II. What Returning Does to the Mind

A. From Cognition to Emotion: The Brain’s Receptivity on Second Reading

The first time we read something—anything—we’re mapping it. What’s happening? Who are the characters? Where is this going? The brain is parsing, decoding, orienting. It’s a useful mode, but not a reflective one.

The second time is different.

By then, the structure is familiar. The plot no longer consumes attention. That frees the brain to make deeper associations—to wander emotionally, not just cognitively. Research in cognitive neuroscience shows that rereading recruits different neural networks, especially those associated with autobiographical memory and emotional integration. We stop just “getting the story,” and start locating ourselves within it.

This is part of a phenomenon called memory reconsolidation—when old neural patterns become fluid again and open to new interpretation. A powerful second or third reading can change not just our understanding of the story, but our understanding of ourselves. This is how rereading becomes, quietly, a form of self-work.

There’s also emotional granularity—the brain’s increasing capacity, with repetition, to differentiate and name feelings more precisely. The first time a story strikes us as “sad.” The second time, it’s “wistful with a flash of envy.” The third time, “grief edged with release.” Each return adds contour to our inner life.

So the story doesn’t just become more true. We become able to hold more truth.

B. Depth Psychology and the Symbol That Waits

Cognitive science offers one lens. But anyone who’s lived through a second heartbreak or reread a childhood diary knows: not everything valuable can be named in the language of data. Stories speak not only to our intellect, but to what Jung called the psyche—the totality of the inner life, conscious and unconscious alike.

In depth psychology, the most potent images are not explanations, but symbols—forms that point beyond themselves, that resist tidy interpretation. A symbol, Jung wrote, is “the best possible expression for something unknown.” Which means: it isn’t meant to be decoded, but entered.

And you can’t enter it all at once.

A good symbol acts like a well: you draw from it at different depths depending on your need. The first reading might offer comfort. The second, confrontation. The third—an unexpected tenderness that was invisible before. As we change, the symbol meets us differently. That’s not a flaw in the story. That’s the function of a living symbol.

The deeper truth is this: when a story contains genuine symbolic life, it doesn’t just say something. It gathers you. Quietly. Across years.

In this way, the story becomes not just something we explore—but something that explores us.

III. Cultural Wisdom on Ritual Reading

We are not the first to notice this.

Many of the world’s oldest traditions have not only accepted, but institutionalized the practice of returning to stories. The Jewish calendar cycles through the Torah year after year, each portion reread, re-sung, re-encountered—not because it has changed, but because we have. The Christian lectionary does something similar, returning the faithful to the same set of texts each liturgical season, as if to say: This moment in your life needs this story again.

And then there is Lectio Divina—an ancient Christian method of spiritual reading that intentionally slows the reader down. One word. One phrase. One question: What is being said to me now? It assumes that the text is not a dead object, but a living voice—and that repetition is not redundancy, but depth.

In oral traditions, stories are passed down not with the aim of novelty, but of formation. A father or grandmother tells the same tale not to surprise the listener, but to shape them. The story becomes a kind of rhythm within the family or the tribe. To hear it again is to remember who you are.

These traditions carry an implicit wisdom: some stories do not finish when you read them. They finish in you, slowly, and when all the right parts of you are available.

IV. What Readers Say: Intuition, Nostalgia, and the Lived Sense of Depth

Not everyone uses the language of psychology or liturgy, but many readers already feel this phenomenon. They may not call it "memory reconsolidation" or "ritual structure," but they’ll say things like:

“I didn’t realize what this meant to me until the second time through.”

“I thought I knew how it ended. Then I read it again, and it landed differently.”

“I keep coming back to this one chapter. It keeps going deeper.”

These aren’t just offhand remarks. They’re intuitive confirmations that rereading is not a fallback—it’s a mode of intimacy. Just like we revisit places we've loved, or remember conversations differently years later, we return to stories because we suspect there’s still more there. And because there’s more of us now to receive it.

Some of the most enduring reader relationships aren’t built on one-time impact but on this quiet loyalty—a sense that the story is waiting, unchanged, for the right moment to open again. Like a friend who doesn’t call attention to themselves, but always has the right words when you need them.

V. How I Try to Write Stories That Are Meant to Ripen

This is the kind of relationship I hope my stories can offer. But if you read no further (and you're welcome to make that choice) consider going back to books you have loved in the past, even if you never reread my short content.

Note: I may slip into saying I “do” this but please understand that what I always mean is that I try to do this, and hope one day to succeed. I’m not aiming to rival literary giants or craft masterpieces for the ages; my focus is on creating small, intentional stories that resonate deeply with those in moments of transition. If I succeed even slightly in writing as I intend, I believe rereading these stories as a ritual can unlock unexpected benefits—quiet shifts in perspective, emotional clarity, or a renewed sense of self.

I write for the shelf or the drawer or email folder marked "reread". My dream is writing that tucked-away email you’ll reread on a hard morning. These stories aren’t meant to dazzle on first pass. They’re meant to stay with you.

That’s why I design them with room to breathe—moments of silence or ambiguity, with images that may not fully register until a second or third reading. I leave space on purpose. Because I trust the reader’s unconscious to do something with that space. What this means is that you will likely find yourself saying “I don’t get it.” I’m ok with that. It’s not your final answer.

I seed symbols early—not to create puzzles, but to create echoes. I write characters whose gestures hint at something unresolved. I let certain truths emerge only when the reader is ready to see them. Sometimes that means risking a softer first impression. But the tradeoff is depth. Return. Recognition.

These are stories for people in transition. People facing grief, reinvention, spiritual quiet, or emotional unraveling. Not everyone is ready for that the first time they read. But many, or at least some, will come back. And when they do, I want the story to meet them where they are now.

VI. A Different Model for Storytelling: Ritual, Not Scroll

We live in a culture shaped by speed. Most storytelling now is designed for one encounter only—scroll, swipe, move on. That’s not a criticism; it’s just the shape of the medium. But it means that much of what we consume is optimized for impact, not integration.

The stories I’m speaking of—those worth returning to—don’t behave like that. They aren’t engineered to impress or provoke. They are shaped more like seasons or liturgies. Their rhythm isn’t urgency. It’s familiarity.

There’s a different kind of comfort, a different kind of transformation, that comes from hearing something again. Not because you forgot, but because you’ve grown. A story heard at seventeen becomes a mirror at forty. Not because it changed—but because you did.

In this model, the story is not a one-time event. It’s a structure that walks with you. You don’t extract a takeaway and move on. You live with it. Let it travel inside you.

VII. The Story Is Waiting For You

Sometimes I wonder whether these stories are actually complete when I finish writing them. Or whether they finish themselves slowly, in someone else’s life, over time.

I’ve come to believe that some stories are not finished when they’re read. They’re finished when they’re returned to.

So if a story stays with you, unsettles you gently, or feels slightly unfinished—good. That means it’s still working. That means it’s alive. You don’t have to understand it all at once. In fact, I hope you don’t.

Because the story will still be here when you come back.

And when you do—it will be different.

Because you will be.